Over the last decade, a prominent question in procurement law has been whether development agreements are subject to public sector procurement law. Since the European Court of Justice’s influential case of Auroux v Roanne in 2007, it is generally presumed that development agreements are subject to procurement law, with the acknowledgment of a particular caveat; an agreement will not be a works contract unless it contains an enforceable contractual obligation on the developer to see that works are done.

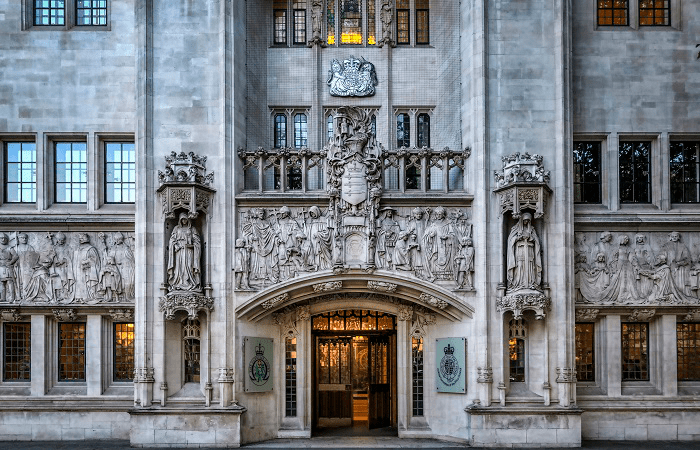

In December 2018, a landmark judgement by the Court of Appeal challenged this widely accepted rule and the way that development agreements are procured with public authorities. In the case of Faraday Development Ltd vs West Berkshire Council, the Court made the first declaration of ineffectiveness seen in an English public procurement case since the remedy was introduced in 2009.

In this blog, Procure Partnerships Key Account Manager Faye Dolan reviews the lesson learnt from this important judgment and discusses how it has put into question a previously well-established area of procurement law.

Faraday Development Ltd vs West Berkshire Council; how it began…

In 2013, St Modwen Developments Limited won an agreement worth approximately £135 million with West Berkshire Council to regenerate an area of council owned industrial land. Faraday Development Limited owned a leasehold interest in some of the buildings and had obtained planning permission to develop. Bidding as part of a joint venture company, Faraday lost out to St Modwen in a bidding process to develop the wider estate.

A requirement of the agreement between West Berkshire Council and St Modwen was that, when ready, St Modwen must apply for planning approval for the contract work in each of their development plots. Once a plot appraisal was approved, St Modwen could then choose to enter into obligations to acquire and redevelop the land, but until that point, was under no legal obligation to do so.

The High Court Appeal

On 4 September 2015, Faraday challenged the Council’s decision, claiming that the development agreement was a public contract and as such the Council should have complied with the relevant public procurement legislation. Faraday accused the Council of trying to avoid having to follow public procurement legislation by not imposing enforceable obligations on St Modwen Developments Limited.

Faraday’s challenge was rejected by the High Court, who stood firm that the Council had complied with its duties and that the development agreement did not constitute as a public works or services contract. The court also rejected the idea that the Council should have imposed an enforceable obligation for St Modwen Development to carry out further development of the land.

The Court of Appeal Ruling

Faraday took the High Court decision to the Court of Appeal. The Court of Appeal agreed with the High Court that the development agreement was not a public works contract at the time it was concluded because it did not contain any immediately enforceable obligations to carry out works, contingent obligations did not count as they lay within the contractor’s control. The Court of Appeals did not believe that the development agreement was a sham, or that the Council had intentionally tried to avoid activating public procurement regulations by not immediately enforcing obligations on the developer.

However, despite agreeing with the High Court on these points, the Court of Appeal ruled that the development agreement was deemed unlawful. Although the development agreement was not a works contract at the time it was entered into, West Berkshire Council had put itself in a position in which it would be subject to works contracts if and when St Modwen triggered each phase. At this point, it would be too late to carry out the required procurement procedures. The contract had been entered into without the required advertising or competition and was deemed as being in breach of the Public Contracts Regulations (actual or anticipatory), and in breach of public law, because it involved the Council in effect agreeing to act unlawfully in the future.

For the first time in England and Wales, the Court granted a declaration of ineffectiveness under procurement law and ordered the payment of a civil financial penalty by the Council, which was fixed at just £1. The declaration of ineffectiveness meant that the existing contract was no longer valid from the date of the judgment onwards.

What can we learn from this case?

This case provides some clarity over the controversial question about whether private development agreements are subject to public sector procurement law. Contracts for ‘works’ let by contracting authorities are subject to procurement law but contracts which only deal with transfers of land are not. Development agreements occupy a bit of a ‘grey area’, compounded by the fact that they are often long-term agreements which are subject to many changeable and unpredictable factors, such as the availability of funding, planning restrictions, fluctuations in the housing market and political agendas and priorities.

However, the clear conclusion procurement practitioners can take from the case is that including an option for the developer to ‘trigger’ future contractual obligations, is now unreliable. In the Faraday case, St Modwen would only be bound by enforceable development obligations once they had triggered them by serving a notice to West Berkshire at each new phase of development. Authorities must now choose between having no obligations at all (meaning they cannot directly require that any particular works are carried out) or treating this type of agreement as subject to procurement law.

It is essential that public bodies consider whether an agreement may trigger the public procurement regimes in the future, at any stage of the agreement, to check they are not unintentionally bypassing procurement laws. ‘Optional’ development agreements do not overrule procurement law.

Voluntary Transparency Notices are only effective with full disclosure.

Another important finding from the case was in relation to VEATs (voluntary transparency notices).

West Berkshire submitted a VEAT to the Official Journal of the European Union as confirmation that they did not believe they were required to advertise the contract opportunity or run a regulated procurement competition. A valid notice is supposed to prevent the contract from being declared ineffective in the future. However, in this case, the VEAT was described as not being sufficiently detailed. It did not mention that obligations could be triggered by an option exercised by the developer and so was not considered to be a full disclosure. As such the VEAT did not provide any protection and the contract was still declared ineffective.

The Faraday case was a stark lesson in the consequences of misinterpreting procurement laws and stresses the importance and responsibility of developers and advisers to work closely with public authorities to ensure diligence.